1. INTRODUCTION

Concurrent delay is a vexed and complex technical and legal issue. The challenge is to equitably determine: 1) the contractor’s entitlement to a time extension as a result of an owner-responsible delay event (liability) and recovery of the contractor’s extended time-related costs (damages) that result from such delays; and 2) the owner’s recovery of its actual delay or liquidated damages when the contractor fails to complete its work by a contractual stipulated completion date as a result of a contractor-responsible delay event that is concurrent to the owner-responsible delay event.

Construction contracts often do not expressly provide direction as to the parties’ agreement when there is concurrent delay. Most simply require the contractor to provide notice and specifics when an owner-responsible delay event occurs. The owner then must determine the appropriate time extension, if any, to which the contractor is entitled. However, the owner may be reluctant to grant the contractor an extension of time if the contractor had caused its own delay during the same period. The owner also must consider its position with respect to its actual or liquidated damages as a result of the contractor-caused delay. A dispute may then occur as to whether the contractor is entitled to any extension of time if he also caused delay in the same period.

Legal jurisdictions around the world differ as to the treatment of the liability and damages aspects of concurrent delay. To help unravel the complexities of this issue, the following topics are discussed in this article:

- Concurrent Delay Defined;

- Treatment of Concurrent Delay in Various Legal Jurisdictions;

- Allocation of Delay Responsibility when Concurrent Delay Occurs;

- Factors that Influence the Identification and Quantification of Concurrent Delay;

- Pacing vs. Concurrent Delay; and

- Practical Guidelines

2. CONCURRENT DELAY DEFINED

The term “concurrent delay” is commonly used to describe circumstances where different causes of delay overlap during a period of time or schedule window.1 As such, concurrent delay could occur during a window if a delay that was caused by the owner2 is on the same activity path or a parallel activity path as a delay that was caused by the contractor.3 If the owner-caused delay and contractor-caused delay affect the same activity or affect different activities on parallel activity paths which are equally critical,4 and as such the owner-caused delay and contractor-caused delay would each have delayed the completion date of the project, the delays are said to be concurrent.

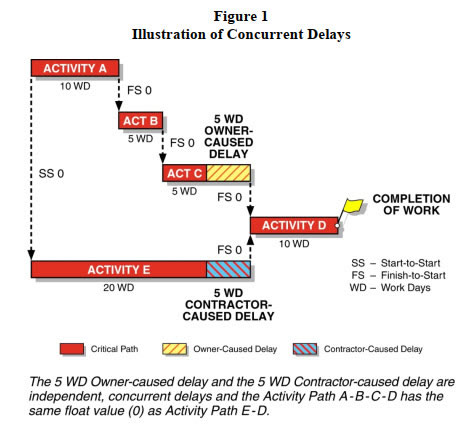

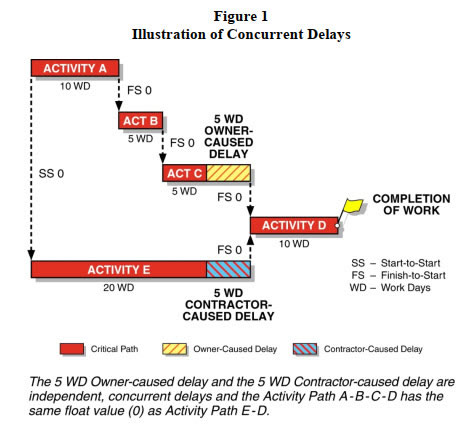

For example, as shown in Figure 1, two parallel activity paths are each delayed by five work days during the same window by separate causes, one delay was caused by the owner and the other delay was caused by the contractor, and both affected activities have the same float value. The two 5-work day delays are concurrent.

This situation is of significance when one cause of the delay is at the owner’s risk, while the other, competing cause of delay is at the contractor’s risk, and where both causes may be regarded as having caused or contributed to the delay on the project.

His Honour Judge Seymour Q.C., in Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v. Frederick A Hammond (No.1), states:

However, it is, I think, necessary to be clear what one means by events operating concurrently. It does not mean, in my judgment, a situation in which, work already being delayed, let it be supposed, because [the Contractor] has had difficulty in obtaining sufficient labour, an event occurs which is a [Employer’s time risk event] and which, had [the Contractor] not been delayed, would have caused him to be delayed, but which in fact, by reason of the existing delay, made no difference. In such a situation although there is a [Employer’s time risk event], ‘the completion of the works is [not] likely to be delayed thereby beyond the completion date’. The [Employer’s time risk event] simply has no effect upon the completion date. This situation obviously needs to be distinguished from a situation in which, as it were, the works are proceeding in a regular fashion and on programme, when two things happen, either of which, had it happened on its own, would have caused delay, and one is a [Employer’s time risk event], while the other is not. In such circumstances there is a real concurrency for causes of the delay.5

3. TREATMENT OF CONCURRENT DELAY IN VARIOUS LEGAL JURISDICTIONS

In this section, the common legal practices regarding the treatment of concurrent delay is summarized in the following jurisdictions:

- U.S. law;

- English law;

- Scots law;

- Canadian law;

- Hong Kong law; and

- Australian law.

3.1 THE U.S. BENCHMARK

A primary tenet of construction contracts is that there is an implied warranty in every contract that neither party can delay or hinder the timely performance of the other party.6 In the case of concurrent delay, it is argued that both parties have delayed or hindered the timely performance of the contract.

U.S. courts and arbitration proceedings offer three approaches to the handling of concurrent delay: time but no money; apportionment; or responsibility based on a critical path delay analysis.

One author writes that the “time but no money” principle traces back to early 1900s U.S. cases when a strict rule against apportionment applied.7 In one case, the courts could not apportion “with any degree of certainty.”8 In another case, the court found that “where both parties to a contract are responsible for delay in its performance the court will not undertake to apportion the responsibility for delays.”9

The rule against apportionment was later abandoned because of the frequent use of liquidated damages clauses, the complexity of the contractual relationships, and a belief that the older rule was too harsh in its application.10 Thus, U.S. courts will apportion delay damages when evidence permits the segregation of costs resulting from each party’s causes.11 However, courts will not find for apportionment if the segregation of delay costs is impossible.12

Critical path delay analysis offers an alternative to apportionment in that it offers the best evidence of cause-effect analysis of time impacts, as explained in Section 4 herein.

Several cases are instructive as to U.S. law with respect to concurrent delay.

The contractor in Blinderman13 was seeking additional expenses and a time extension in respect of delays to the completion date. The contract provided that an adjustment should be made to the contract price for any increase in costs caused by suspension, delay, or interruption by the government, except where the works would have been suspended, delayed or interrupted by any other cause, including the fault or negligence of the contractor. The court found that the contractor contributed to the delays and held that:

Where both parties contribute to the delay “neither can recover damage, unless there is in the proof a clear apportionment of the delay and the expense attributable to each party.” Coath & Goss Inc. v. United States, 101 Ct.C1.702, 714-15 (1944); Commerce International v. United States, 167 Ct.C1.529, 338 F.2d.81, 90 (1964).

Generally, courts will deny recovery where the delays are “concurrent or intertwined” and the contractor has not met its burden of separating its delays from those chargeable to the Government.

The ruling in Blinderman means that neither prolongation costs nor liquidated damages are recoverable where apportionment is not possible, so an extension of time will be granted in such a case.

In Beckman Construction Company,14 the contractor sought costs associated with delay. There were concurrent delays. It was held:

Where delays for which the Government bears responsibility are concurrent with other delays due to non-compensable causes, a contractor may not recover delay costs where the non-compensable delays cannot reasonably be separated from those delays for which it is entitled to receive compensation.

It was determined that the contractor bears the burden of proving, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, the extent of delay caused by the compensable actions of the government.

In Cline Construction Company,15 also involving a claim for delay costs where there were concurrent delays, it was held:

Concurrent delay does not bar extensions of time, but it does bar monetary compensation for daily fixed overhead costs of the type claimed by Cline because such costs would be incurred on account of the concurrent delay even if the Government responsible delay had not occurred.

This ruling is consistent with Blinderman; on the facts of the case, the delay events took place at the same time (i.e., there was “true concurrent delay”) and it does not appear that the compensable and non-compensable delays could be separated. It is for this reason that an extension of time would be due. If the compensable and non-excusable delays could have been separated, Blinderman would have required that there be no extension of time for the non-excusable delay, and the owner would have been entitled to damages for the contractor’s non-excusable delay.

This finding was held to be the case in Toombs.16 The contractor sought remission of the liquidated damages deducted from monies otherwise due to him on the ground that when both parties are at fault and responsible for the delay, liquidated damages cannot be recovered from the contractor. It was held that the contractor:

…paints with too broad a brush. When it is reasonably possible to apportion the delay among the various causes, liquidated damages may be assessed notwithstanding concurrent causes attributable to both parties.

In William F. Klingensmith Inc.,17 the contractor sought a contract time extension plus impact costs where there were concurrent delays. It was held:

The general rule is that “[w]here both parties contribute to the delay, neither can recover damage[s], unless there is the proof of a clear apportionment of the delay and expense attributable to each party.” Blinderman, 695 F.2d at 559, quoting Coath & Goss. Inc. v. United States, 101 Ct.C1.702, 714-715 (1944). Courts will deny recovery where the delays are concurrent and the contractor has not established its delay apart from that attributable to the government.

In Rivera General Contracting,18 there was a claim for delay allegedly caused by the government. There were competing causes for the delay. The contract contained an adjustment of price clause similar to that in Blinderman. It was held:

Where Government caused delays are concurrent or intertwined with other delays for which the Government is not responsible, the contractor cannot recover delay damages. This principle applies equally to delays attributable to a change as to ordinary damages for delays.

Again, this is not inconsistent with Blinderman. On the facts, the delay events took place at the same time (i.e., there was “true concurrent delay”) and although the government admitted that it may have been partially responsible for some of the delays experienced, there was no evidence to demonstrate that the contractor had incurred any increased cost as a result of the governmentcaused delay. Therefore, there was no issue of separating the compensable from the noncompensable delay.

In Hood Plumbing,19 claims were made for delay costs and remission of liquidated damages. There were concurrent delays. It was held in relation to the claim for additional costs:

In order to recover for alleged compensable delay by the Government, a contractor must demonstrate, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, both the extent and cause of such delay. … When delays by the Government are intertwined or concurrent with delays that are not compensable, neither the Government nor the contractor may recover unless the delays can be separated or apportioned.

With regard to the remission of liquidated damages, it was held that the contractor’s delay exceeded the period of delay caused by the government and on that basis, liquidated damages could be assessed. This is not inconsistent with the principle that liquidated damages are not recoverable if delay cannot be apportioned; the assessment made in this case did amount to an apportioning of the delay.

CG Norton Co. Inc.20 was another case in which the contractor claimed delay costs plus the return of liquidated damages deducted by the government. There were several reasons, attributable to both the contractor and the government, underlying the sub-contractor’s failure to perform on time, which caused delay to completion. It was found that the reasons were “substantially chargeable” to the contractor’s conduct, whilst the government’s interference was “minimal” and a direct result of confusion fostered by the contractor’s actions. On that basis, it was concluded that the additional costs claimed did not flow from the government’s conduct.

Despite this finding on the facts, it was held that there was a concurrent delay and with regard to the assessment of liquidated damages, the court referred to the judgment in AMEC Processing Equipment Co. v. United States,21 which provided:

. . . Download PDF article to read the remainder of the article and all footnotes.

Long International provides expert claims analysis, dispute resolution, and project management services to the Process Plant Engineering and Construction industry worldwide. Our primary focus is on petroleum refining, petrochemical, chemical, oil and gas production, mining/mineral processing, power, cogeneration, and other process plant and industrial projects. We also have extensive experience in hospital, commercial and industrial building, pipeline, wastewater, highway and transit, heavy civil, microchip manufacturing, and airport projects.

Richard J. Long, P.E., is Founder and CEO of Long International, Inc. Mr. Long has over 40 years of U.S. and international engineering, construction, and management consulting experience involving construction contract disputes analysis and resolution, arbitration and litigation support and expert testimony, project management, engineering and construction management, cost and schedule control, and process engineering. As an internationally recognized expert in the analysis and resolution of complex construction disputes for over 30 years, Mr. Long has served as the lead expert on over 300 projects having claims ranging in size from US $100,000 to over US $2 billion. He has presented and published numerous articles on the subjects of claims analysis, entitlement issues, CPM schedule and damages analyses, and claims prevention. Mr. Long earned a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Pittsburgh in 1970 and an M.S. in Chemical and Petroleum Refining Engineering from the Colorado School of Mines in 1974.

©Copyright - All Rights Reserved

DO NOT REPRODUCE WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION BY AUTHOR.